Did you know that over 1400 species of fish can be found in New Zealand waters? Nearly 300 of these species are endemic, meaning they’re found here and nowhere else.

The huge diversity of our fish species could fill many textbooks. If you’re out on the water this summer you’re most likely to spot common species such as pākirikiri/blue cod, tāmure/snapper, and whai repo/eagle ray. Whatever you spot, learning how to identify marine species will increase your familiarity and connection to the ocean, or at the very least impress your friends.

Here you can learn some of the protected species of sharks, fish, & rays found in our oceans.

Fishes

Fishes come in three types: bony, cartilaginous (having skeletons makes of cartilage, much like your nose and ears, and jawless (like the hagfish, these fish often look like giant worms).

Of all of our bony fishes only two are protected. They are both grouper – the giant or Queensland grouper and the spotted black grouper.

Living up to its name, the giant grouper can grow up to 3 meters long and weigh up to 400 kilograms.

📷: John Anderson

Giant groupers are pretty rare to spot in New Zealand, as they prefer the warmer waters of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. However, if you do see one, look for a large mouth, yellowish, rounded fins with dark spots, and a first dorsal fin very low on the body. The juvenile groupers have a striking sense of fashion which fades as they grow older:

📷:Image Citron / CC-BY-SA-3.0

This dramatic colouring helps them to hide among brightly coloured corals and sponge gardens while they are small enough to be a light snack.

All giant groupers are born female. Some will become male as they age, if there aren’t enough males around to maintain the population.

Final fun fact: a giant grouper named Bubba, who passed in 2006 at the age of 24, is considered to be the first fish to have undergone chemotherapy and became somewhat of a hero to cancer patients.

The spotted black grouper is most common at the Kermadec Islands and Three Kings Islands, though they have occasionally been spotted as far south as Hokitika. They are considerably smaller than the giant grouper, reaching about 2 meters long and weighing up to 80 kilograms. Most however, are less than 1 meter long. Look for the distinctive on dark bands along their back, angled toward to the head and a dark saddle in front of the tail. Spotted black grouper are capable of rapid colour changes, varying from almost completely white to black within a few seconds.

Sharks

Sharks are cartilaginousfish, meaning their skeleton is made of cartilage rather than bones.

Just one of at least 64 species of sharks found around New Zealand, the ururoa / great white (sometimes called white pointer) gets a lot of airtime for being one of the most dangerous. However, it’s in decline and considered ‘vulnerable’ due to fishing, habitat loss, and pollution.

📷: Clinton Duffy/DOC

Some top tips for identifying great whites: look for a conical snout, large dark eye, a sharp colour change between the upper body and belly, a tail with an upper lobe slightly longer than the lower lobe, dark tips on the underside of the pectoral fins, large triangular teeth and a pretty dramatic overbite. The maximum reported size is 7 m length, although individuals over 5.5 m are rare.

To be fair, if you’re in the water and you see a great white, you’re probably not going to be looking closely for features to identify. If you encounter one, the best thing to do is stay calm and leave the water as quickly as possible.

📷: Elias Levy / CC-BY-2.0

📷: Johan Lantz / CC-BY-SA-3.0

📷: Francis Perez

📷: Derek Keats / CC-BY-2.0

The oceanic whitetip shark is sometimes confused with the great white due to the great white’s alternative name the white pointer. However, the two species are strikingly different. The oceanic whitetip has a flattened, broadly rounded snout, exceptionally large dorsal and pectoral fins with rounded tips, and conspicuous white tips to most of the fins. Surprisingly, new born pups have black instead of white tips to their fins. Maximum size is around 2.7 m.

The deepwater nurse shark is a rarely seen species, preferring water 100 meters or deeper. They can be identified by their two dorsal fins and greyish-brown colouring.

The whale shark is the largest fish in the world, reaching up to 18 meters – though you’d be extremely luck to spot one longer than 12 meters. They are easily recognisable by their giant, wide mouth and distinctive stripes-and-spots pattern.

📷: Nicholas Lyndall Reynolds CC-BY-SA-4.0

Rays

Rays are also cartilaginous fish but have different body shapes and different ways of swimming, feeding, and breathing.

The spine-tailed devil ray, despite its feisty name, is a filter feeder which eats plankton. They are most commonly seen in small groups, though there have been reports of spectacular groups of several hundred.

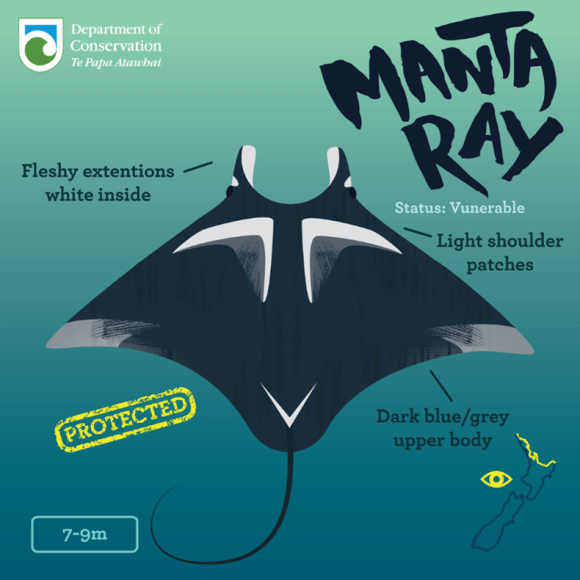

If you see a ray swimming or resting at the surface, remember to look for: fleshy extensions off the head which are white on the outside, a wide black headband, and a tiny white tip on the pectoral fin.

These are important differences, as the devil ray is commonly mistaken for its close relative the manta ray. Manta rays can reach unbelievable sizes – up to 9 meters from wingtip to wingtip. Their fleshy extensions are white on the inside, and they have distinctive shoulder patches.

They’ve also got the largest brain-to-body weight ratio of any fish – very smart indeed.

📷: Arturo de Frias Marques / CC-BY-SA 4.0

Remember, DOC has many resources on marine fish and reptiles, as well as identification guides for protected species.

Spectacular photos. We have to take much greater care of our poor sharks.